The research:

Leow, R. P. (2008). Input enhancement and L2 grammatical development: What the research reveals.

(Open access, see here)

Type of research

A meta-analysis of research into the effectiveness of different input enhancement techniques. The range of studies were published from 1991-2007.

What is input enhancement?

Input Enhancement (IE) refers to techniques used to draw learners’ attention to features of the target language. The term was originally coined by Mike Sharwood-Smith (1991, 1993), whose work is open access here.

Leow points out that input enhancement is quite an open-ended concept, but examples include:

- Input flooding (ensuring lots of examples of target language appear within a given text, making it more salient)

- Textual enhancement (highlighting or bolding certain text to draw attention to it)

- Use of gestures to facilitate correction (I wouldn’t have thought of that as input enhancement until I read this study tbh)

- Providing explicit information on certain target language

- etc

Research has usually focused on two types of input enhancement that are easier (!) to test empirically. Leow categorises these types as the following:

Conflated input enhancement: this is enhancement plus some kind of explicitness. An example given is when target language is highlighted (bold, underline, etc) in a text, and is accompanied by a teacher explanation, information regarding a grammar rule, and so on. In studies, control groups are given neither condition (enhancement or explicit information/instruction).

Non-conflated input enhancement: Enhancement is given, for example some kind of highlighting of the target language in the text, but no explicit or instruction/information appears alongside it. The control groups get no enhancement.

By the way, the highlighting-the-text thing is generally called ‘typographical text enhancement’.

Leow’s meta-analysis

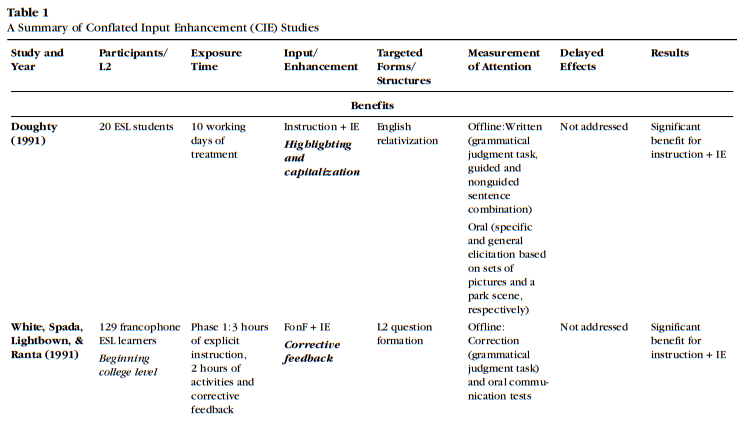

Seven of the studies analysed were considered to be testing the effects of conflated text enhancement. The studies are all summarised in a table like this (see text for full breakdown):

Analysis showed that ‘the majority of studies found overall benefits for this type of enhancement’ (2008:19). However, the findings are hedged by this comment on research design:

There are studies in which exposure time to enhancement techniques was 20 minutes only, 1 hour only, or just 2 classroom hours. Longitudinal studies against a control group over the course of a term or so would have been far more insightful, or at least some more studies that assessed delayed effects. Leow could only analyse the studies that were available, and it seems that a) there weren’t many, b) they were too varied, c) they were too short-term. Although some had a pretty big sample size.

You may have noticed my (!) earlier at the suggestion that certain types of text enhancement are easier to test empirically. Leow mentions that while text enhancement test groups may have shown improved performance in recognising/using grammar forms in post-tests, it was hard to attribute this improvement directly to text enhancement techniques. There wasn’t enough data gathered in real-time to establish whether learner attention was drawn to enhancements, and possible effects may have been conflated with other techniques used alongside, such as feedback, discussion, or explicit instruction alone.

Studies into non-conflated text enhancement conditions mostly assessed the impact of using visual cues (bold typeface, italics, capitalisation, etc) for saliency, and most used input flooding to increase the amount of exposure to target items. Again, of the studies analysed, very few lasted longer than a few weeks, most were less than an hour, and few assessed delayed effects. Overall findings suggested there were no significant benefits to L2 development of using text enhancement without some aspect of explicitness in tandem.

Leow suggests that one explanation for the lack of effect might be that learners may not have attempted to process the enhanced text for grammatical information, but perhaps instead for general meaning. Fair point.

The overall findings

- Text enhancement may have some benefit when accompanied by some form of additional (often explicit) input to raise learner attention

- It probably has to be done over a period of time, not just as a one off

- That said, delayed effects are unclear. Underresearched also.

Pedagogical implications

- ‘Given that L2 learners typically read for meaning, detailed attention to enhanced forms should be promoted after L2 readers have had a chance to perform this content-based task.’

- Don’t just use text enhancement, have some instructional attention-focusing protocol to go around it.

My context

Damn it. Text enhancement is one of those techniques I advocate for a few reasons, not just regarding grammar development but also for vocabulary development. It’s always been one of those things that I assume draws attention and focus to input, and seems intuitive, yet really seems to lack conclusive empirical evidence.

Still, I mention it in teacher notes…

And resource books…

… because I see logic in the (aforementioned) work of Sharwood Smith, plus the ideas of this guy…

… who co-authored one of the studies in the Leow’s meta-analysis. I push for text enhancement in resources that I oversee for publishers, yet they ignore me…

… so said resources end up with the explicit aspects alongside them but not the textual enhancement…

And I may not be the one to write the teacher notes alongside this, so the message of drawing attention to certain salient features may get lost or ignored…

But then given the lack of clear evidence from studies into text enhancement, I’m not sure why I harp on about it so much. Does empirical evidence always matter when you feel something serves a purpose? No. Not if you have street data to back it up – your own observations/action research over time that suggests a certain technique is of value. But I don’t have that either – for my learners. All I have is experience of being a language learner myself and, when encountering input enhancement, moments when I’m like ‘aaaaaaah, look at those bold bits… so this seems worth looking at, oooh I can see there’s a kind of pattern going on there in the language use, ahhh I should kinda work out what’s going on there ….’

And that’s the type of qualitative ‘data’ that is lacking in order to validate text enhancement as a technique. Who is going to bother getting shed loads of ‘think aloud’ data from learners to establish whether making salient features in a text stand out has some benefit?

I’m interested in the fact that the (loose) evidence in favour of text enhancement stresses that it works well when coupled with some other consciousness-raising technique – like explicit information or instruction. It feels like the type of thing I’ll shoehorn into some kind of coursebook promo session for a publisher down the line.

Anyway, in summary:

This interesting yet fairly inconclusive meta-analysis is unlikely to stop me using both conflated and non-conflated input enhancement, but is likely to make me question why (on both counts). And my answer will probably be ‘because… habit’, or ‘because… implicit learning’. And I think I’m okay with both, tbh.

Categories: General, reflections, teacher development

Leave a comment