I’ve heard plenty of EAL teachers dissing the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). ‘It’s not relevant for assessing EAL learners’, ‘it’s too general’, etc. This is another of those areas in which I kinda understand the sentiment, but feel like we are talking at cross purposes a bit.

In my view, the CEFR itself is certainly relevant to, and compatible with, the teaching of EAL. To go one step further, I’d say it would be the most relevant assessment tool for EAL, with some tweaks to accommodate more reference to academic language development. The reason that the value of the CEFR as an assessment tool is questioned is (IMHO) less to do with the CEFR, and more to do with the testing practices associated with it.

What is it that makes the CEFR more relevant than we think? What might it be that holds some EAL specialists back from appreciating its value? Eeek… I better come up with an argument now!

The CEFR is extremely comprehensive

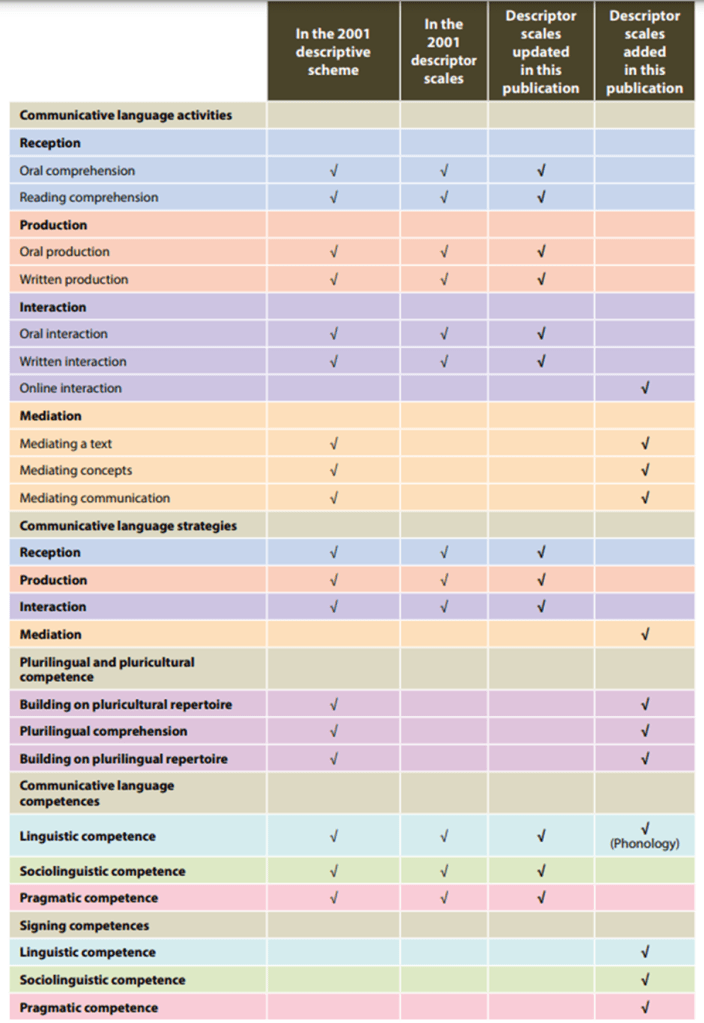

1800 descriptors, around 16 strategies or competences, 34 different scales. The amount of thought that has gone into the CEFR is admirable. Is it too comprehensive to be used practically for ongoing assessment? Perhaps. Yes. Yes!

I find that much of the criticism levelled at the CEFR is to do with reductive versions of it. The Council of Europe don’t help themselves on that front, reducing their highly detailed framework down into uber-concise self-assessment grids like this:

Despite the effort that must have gone into creating the framework, both the CoE and publishers using the CEFR to structure their resources seem intent on simplifying the content. If we (as teachers) were encouraged to view the primary resource, more EAL teachers might realize that it is *vastly* more detailed and *vastly* more relevant than they might expect.

It’s action-oriented

There are not just descriptors for tick-box sake either. While it’s fair to say that some of the descriptors are a tad vague or general, for the most part they are demonstrable and applicable to language users, not just language learners. Those of us using WIDA or Bell frameworks have become accustomed to descriptors that relate directly to classroom and academic contexts. What we might occasionally lose sight of in such contexts is that being able to do XYZ in a classroom context is, quite often, specialized application or *real-world* skills. The CEFR is all about real world application, and the wording is often careful enough in that it incorporates ‘academic’, ‘specialised’ (etc) contexts.

It’s pragmatic

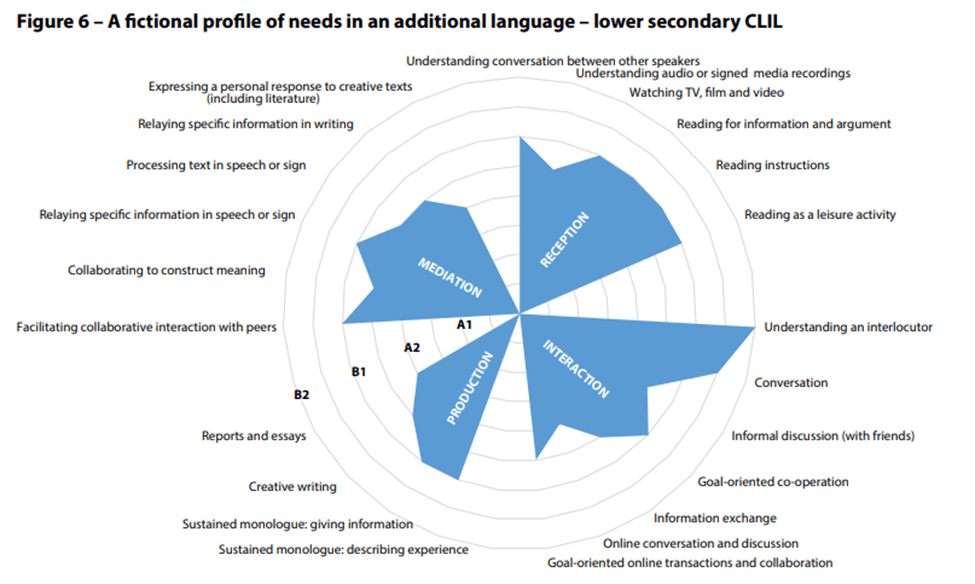

The descriptors are arranged in four modes of communication: interaction, mediation, reception, production. For me, there is something far more intuitive about these categories than, say, using ‘the four skills’ (listening, speaking, reading, writing) as organizing categories – which tends to happen during that process of simplification. Yes, listening may be a receptive skill, but it’s also one that feeds into interaction. Yes, writing would be a form of production, but writing with a deeper understanding of field, tenor, and mode in order to impart meaning may fall into the category of interaction or even mediation.

The organization of the CEFR (in my view) attempts to account for the fact your typical ‘four skills’ aren’t mutually exclusive. Communication and language-in-action seems to be the driving principle of the CEFR – whether that message is truly realized through language testing systems that align to the CEFR is, in my view, questionable.

It’s become more relevant to EAL contexts

A glance at the additions and updates to the CEFR shows how the Council of Europe acknowledge more contemporary research into communicative, pragmatic, social and linguistic competences:

As mentioned, CEFR is action-oriented. There is not just an acknowledgement of the importance of plurilingual competence and successful mediation, there are descriptors within the framework outlining how competence is demonstrated in these areas.

It also takes into account the jagged profiles of many EAL learners. Not only do the authors of the CEFR critique the CEFR levels as a simplification, they clearly outline the reality regarding learner proficiency:

Again, the CEFR itself *does seem* fit for purpose. However, many level tests that purport to be assessing ‘CEFR levels’ do not align with CEFR modes of communication, and assess general competences without taking into account learner needs in the context, their language backgrounds, etc. In the Companion Volume to the CEFR, users are encouraged to emphasise learner ‘growth in relevant terrain’ – by which they mean the modes of communication that are most relevant to their context. This does not align with how many exams bodies approach assessment based on CEFR levels.

Many EAL teachers don’t realise that they are using CEFR-related assessment tools anyway

One confusing thing about the kind of ‘CEFR!’, ‘No! Bell!, ‘NO! NASSEA!’ arguments is that most alternatives to CEFR are just reductive versions of the tool anyway – with minor tweaks. If you were to look at a copy of, say, the Bell Assessment Framework and search for key phrases from their descriptors in the searchable CEFR descriptors spreadsheet, you’ll find plenty of matches. What’s more, you’ll probably find them under more relevant headings that just (again) ‘the four skills’. I’ll save you the hassle by picking some at random. Let’s go with Bell Band C Listening…

| Bell Band C descriptor | CEFR descriptor that aligns |

| C1 – Can understand the main points of radio news bulletins and simpler recorded material about familiar subjects delivered relatively slowly and clearly | Descriptor number 73, under the mode of ‘Reception’, listed as a B1-level target |

| C2 – Can follow and negotiate with other pupils during group work | Descriptor number 525, referring to negotiating in academic life, under the mode of ‘Interaction’, listed as a C1-level target |

| C3 – Can understand some idiomatic or figurative expressions, but may require explanation | Understanding figurative expressions appears under the mode of ‘Interaction’ at B2+ level. See descriptor 1316 |

| C4 – Can generally follow group discussion and ask for help and repetition where necessary | Pretty much the same descriptor, under ‘sociolinguistic competence’, B2+ (number 1234) |

| C5 – Can follow directions in classroom tasks, paying attention to details | There are a range of 17 descriptors in the CEFR addressing ‘announcements and instructions’, ranging from A1-C1 level targets |

| C6 – Can follow and understand specialised or subject-specific terminology if it has previously been introduced | There are C1 targets related to this under mediation (see targets 812, 854). There a B2+ targets related to understanding specialised articles, topics, and sources, under the modes of Reception and Interaction |

I’m not trying to pick apart the relevance of tools like Bell at all. After all, I choose to use it. However, it is certainly worth pointing out that Bell is just a reductive version of CEFR with some academic tweaks. The plus point is that it is far more practical to use for the purposes of day-to-day, ongoing assessment. The downside is that it, again, it divvies targets up by the four skills (unlike the CEFR), it doesn’t actually do this well (if you consider that speaking targets like C4 ‘commenting on the views of others’ is more about interaction than it is simply ‘speaking’), it’s less comprehensive (when related to the CEFR), and it accounts less for plurilingual competences (when compared to the CEFR).

Why do I care about all this?

I just think there are misconceptions. Using CEFR level testing in EAL context *is* often flawed – but only if we choose to use pre-packaged tests which fail to acknowledge the breadth and depth of the framework itself. The CEFR is an easy target, but that’s just not fair – the Council of Europe can’t ensure that the use of their framework is comprehensive and principled. I haven’t seen a CEFR level test (personally) that genuinely assesses the modes of mediation and interaction, or plurilingual competence for that matter. I’ve certainly seen a lot that reduce language testing to four skills assessed in isolation – I don’t remember that being advocated in the Companion Volume.

An elephant in the room here as well is that, in certain contexts, specific periodic assessment for EAL learners is needed. In SE Asia, plenty of schools offer pull-out provision, accelerated programmes, and so on, and some form of summative assessment is needed. There’s a dearth of this available, and rightly so, because it is probably something that should be made in-house and bespoke to the context. However, time constraints may mean that teachers fall back on CEFR level testing to establish whether learners reach a certain benchmark level. Pre-packaged tests like, say, your KETs or PETs or whatever, are inadequate and irrelevant in the context, but they are a quick workaround and they appease stakeholders.

Moving forward

I suggest that in EAL discussions we stop dissing ‘the CEFR’, and focus specifically on ‘pre-packaged CEFR-aligned testing’ as the object of criticism. Is the tool itself being manipulated? I believe it is. And I’d argue that it underpins much more of what we do, regardless of the specific assessment tool we are using (Bell, Nassea, etc).

I also think that some practitioners need to be more realistic AND honest. I’ve had round-the-houses conversations with teachers who swear blind that CEFR-testing sucks, yet they still use it at the admissions stage for ballpark levelling! It is okay to accept, at times and in certain contexts, that we don’t have better or workable alternatives within our own constraints. It’s what we do from there that matters. We get a snapshot of a learners general ability through something like the Cambridge English Placement Test before they join. Then when they join – how do we go about building full and thorough diagnostic testing?

Regarding periodic testing– can we refer more to the *actual* CEFR itself to shape our own assessments? Can we shake this ‘four skills’ distinction and instead assess the *actual* modes of communication that the CEFR outlines? I feel like we can add layers of disciplinary and academic competences much more easily to modes such as ‘interaction’ than we can ‘listening’ and ‘speaking’ separately. I’m thinking with an oracy hat on here.

Above all, I just think teachers should read the official guidance. Check out the stuff here. Honestly, ‘It’s too general’ is probably the last accusation you’d throw at the CEFR itself after spending a few days processing all that!

Categories: General, reflections

Hello from Vietnam! Thanks for the great post. I’m currently working on my DELTA Module 3 with a specialism in Language Support, and I really appreciate your insights in both your blog and your book Supporting EAL Learners. Thank you, thank you.

I’m wrestling with the IB ATL skills, the CEFR, and WIDA as I try to develop a course not only for my Module 3 but also for my own teaching practice. Reading your posts is helping to guide me through this journey.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really means a lot to get feedback of any kind, but positive fb like this is a real pick me up. Thanks for taking the time to comment and best of luck with Module 3!

LikeLike